Republicans aren’t exactly pumping out fresh policy innovations these days. If anything motivates congressional Republicans, it’s retaking the majority in 2022 and placating the put-upon ex-president Donald Trump. “One hundred percent of my focus is standing up to this administration,” Senate Republican leader Mitch McConnell said earlier this month, succinctly capturing the spirit on Capitol Hill.

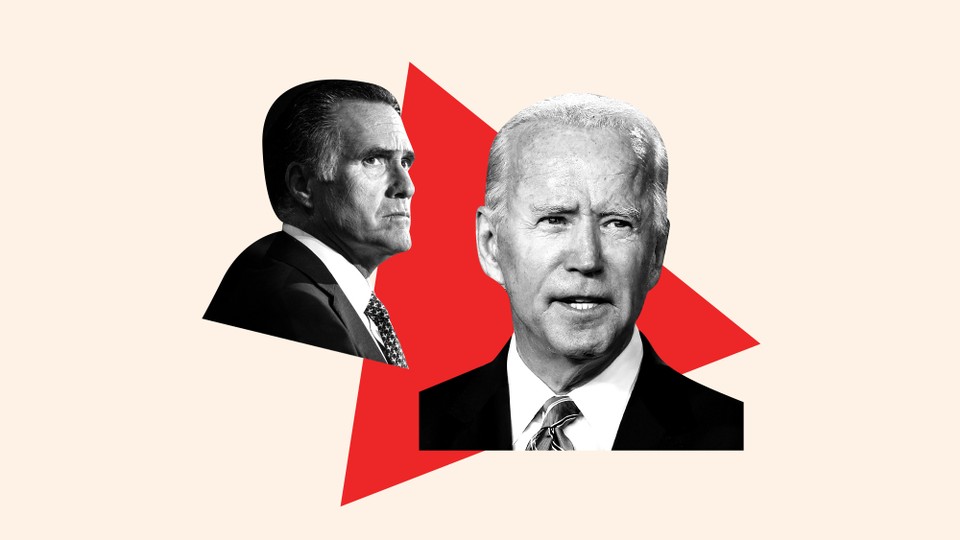

All the more reason that Senator Mitt Romney’s plan to send cash straight to parents raising children is such an anomaly. If you missed Romney’s proposal, that’s no surprise. He released it February 4, the day after House Republicans voted to retain Liz Cheney as the caucus’s third-ranking member despite her apostasy of condemning Trump (a vote of confidence that didn’t stick; Republicans booted her out three months later). The House civil war saturated the news, but it’s not every day that a Republican who’d once been a presidential nominee touts an idea that breaks decisively with party orthodoxy, and, on top of that, invites a Democratic president to solve a problem through that quaint old practice: bipartisan collaboration. At first the White House seemed intrigued. The day Romney released his proposal, President Joe Biden’s chief of staff, Ron Klain, sent a tweet calling the idea “an encouraging sign that bipartisan action to reduce child poverty IS possible.” So why is it stalled?

Romney’s Family Security Act is simple in its design. It provides an annual cash payment totaling $4,200 for households with children up to age 5, and $3,000 for those with kids ages 6 to 17. It tops out at $15,000 a year. Biden has a more expansive plan that shares one important goal with Romney’s: getting money directly to households with kids. They go about it a bit differently, with Biden proposing in his American Families Plan to extend a beefed-up child tax credit until 2025. The benefit is worth $3,600 a year for households with children younger than 6; and $3,000 for older children up to 17. Neither plan requires that parents work in order to receive the money.

[Read: The danger of shortchanging parents]

A strange thing happened when Romney put out his proposal: Most everyone liked it (with a few notable exceptions, which we’ll get to in a bit). Liberals, conservatives, and academics all praised it. Matt Bruenig, the president of the People’s Policy Project, a progressive think tank, called it an improvement over Biden’s plan. Kathryn Edwards, an economist for the Rand Corporation who specializes in women’s-labor-force issues, told me that both the Romney and the White House plans would “do more for child poverty and for the basic needs of families than probably anything in the last 20 years.”

No one can deny the need. Compared with other wealthy countries, America’s aid to families is meager. A UNICEF study released in 2019 examined the extent to which dozens of wealthy countries, including the United States, offered policies that were “family-friendly.” Sweden, Norway, and Iceland topped the list, while the U.S. was the only one that lacked a national paid-parental-leave program. Halfway through Barack Obama’s presidency, one of his former economic advisers, Jared Bernstein, researched the degree to which tax and social-welfare policies in 20 wealthy countries had cut poverty in the mid-2000s. Once all the government policies washed through the system, the U.S. poverty rate ranked the highest, at 17 percent; Sweden and Denmark’s ranked the lowest, at 5 percent. (Bernstein is now a member of Biden’s Council of Economic Advisers). European countries “have much lower rates of child poverty than the U.S.,” Mark Rank, a social-welfare professor at Washington University in St. Louis told me. “One big reason is because they have these programs. For the U.S. to be considering this is pretty radical. It really goes against the grain of how we often try to address poverty.”

And that may explain a hard reality about Romney’s plan: It’s going nowhere. It stands virtually no chance of getting the 60 votes required under Senate rules. The White House now seems leery of it. More than three months after Klain’s encouraging tweet, not much action has taken place, bipartisan or otherwise. Romney told me he had one brief conversation about the proposal with Steve Ricchetti, the White House counselor. “They have other priorities right now, apparently,” Romney said. “But hopefully, that will come to the top, and we’ll get a chance to sit down and see if we can work out something together.”

The White House declined to make Ricchetti available for comment, sending me instead to two other officials, neither of whom had spoken with Romney or any member of his staff. They voiced doubts that Romney’s allowance was sufficient to meet a family’s needs. And they singled out for criticism a feature that Romney sees as a selling point. Unlike the Biden child-tax-credit extension, which would expire in four years, Romney’s plan would be permanent. He has offered a series of spending cuts to offset the $254 billion cost. One would do away with a $16.5 billion program called Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF) that sends block grants for states to disburse. Another would save $25 billion by eliminating a state-and-local-tax deduction that is especially popular in high-tax blue states. From the White House’s perspective, Romney is giving with one hand, taking with another. “We don’t want it to be a zero-sum game, and [Romney’s] proposal would be a zero-sum game for many low-income families because of the offsets that he’s chosen to pay for his program,” one of the Biden administration officials told me, speaking on condition of anonymity to talk more freely.

[Read: Bidenomics really is something new]

The White House’s policy critique sounds dubious. Romney’s plan would slash child poverty by one-third, according to Rank, who co-authored the book Poorly Understood: What America Gets Wrong About Poverty. What’s more, plenty of problems plague the TANF program. The $16.5 billion funding level hasn’t budged in 25 years, meaning the money hasn’t kept up with inflation. Nor has the cash always reached people who need it most. A report last year by the nonpartisan Pew Charitable Trusts’s Stateline found that “some states are spending big chunks of TANF money on programs used by families who aren’t in poverty, such as on preschool and college scholarships for middle-class students.” As for the state-and-local-tax deduction, the benefits flow mostly to the wealthiest families anyway.

Prominent Republicans are even cooler toward Romney’s idea. A few have come out with family-assistance plans of their own—more tax credits tied to work requirements. Senator Marco Rubio of Florida, who has embraced one such plan, told me, “I don’t know how many Republican votes there would be for just a direct-payment program, which in my mind is not the direction we want to go.”

None of this bodes well for truly bipartisan dealmaking, even though a compromise seems well within reach. After all, the White House and Romney aren’t moving “in the opposite direction,” Jim Kessler, the executive vice president for policy at Third Way, a center-left think tank, told me. “They’re both driving along the same highway. There’s room for some of the things Romney is talking about. He’s talking about a vast simplification, which is appealing. A working poor person’s taxes are more complicated than my taxes.”

Romney could conceivably pitch some other way to pay for his plan, if the White House truly finds his suggestions unpalatable. Politicians tend to say they don’t like to do their negotiating in the news media, but, hey, let’s try. “If there is any portion of that [Romney’s proposed cuts] the White House would like to maintain,” Romney told me as he left the Senate chamber, “that’s certainly possible, and we’ll find other pay-fors.”

Mr. President, what say you?

Maybe the roadblock isn’t so much the particulars of Romney’s plan but the behemoth who still controls the GOP from his exile in Mar-a-Lago. Romney remains an isolated figure inside his party, anathema to the rank and file for voting to oust Trump in both impeachment trials. Cutting a deal with Romney brings precisely one vote: Romney’s. It is doubtful that he can corral anyone else’s. McConnell’s focus is tanking Biden’s poll numbers. Which means that when it comes to smart policy making, the GOP is essentially leaderless. For all Biden’s talk of bipartisanship, he may have already concluded that his best shot at passing anything to help families is “reconciliation,” the parliamentary move that allows the Senate to pass bills with a simple majority vote. If that’s the case, the White House doesn’t really need Romney or any Republican to come on board. “What Senator Romney has proposed is something that Biden could absolutely work with him on,” Ryan Williams, a spokesperson for Romney’s 2012 presidential campaign, told me. “At this point, at least in the administration, they’re not serious about it. Given the low level of outreach to Senator Romney, there’s no indication that they’re interested.”